Eccentric businessmen like Elon Musk want to send people to the Moon or Mars to ensure that humanity survives a global climate disaster.

But in the event of such a catastrophe, what would happen to our planet’s wildlife?

Scientists may finally have an answer as they propose placing a “biorepository” on the Moon to safeguard Earth’s rich variety of animals.

The biorepository would contain frozen cells from millions of “cryopreserved” animal species, from mammals to reptiles, birds and amphibians.

If life on Earth were to disappear, it is hoped that these cells could be cloned to create new life, whether on Earth, the Moon or another planet.

At an average distance of 238,855 miles, the Moon is far enough from Earth to survive a climate collapse that would wipe out animals.

Scientists at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute (NZCBI) in Washington, DC, have outlined their ambitious plan in a paper published in Bioscience.

Although they do not estimate the exact cost of a lunar biorepository, they say it will probably be five times more expensive to set up than one on Earth, but cheaper to maintain.

“Initially, a lunar biorepository would focus on species that are most at risk on Earth today,” said lead author Mary Hagedorn, a cryobiologist at NZCBI.

“But our ultimate goal would be to cryopreserve most of the species on Earth.”

At an average distance of 238,855 miles, the Moon is far enough from Earth to survive a climate collapse that would wipe out the planet’s animals.

But it also has the added benefit of being cold enough to keep animal cell samples frozen, without requiring electricity as on Earth.

Scientists propose locating the “biorepository” in the moon’s particularly cold polar regions, which have craters that never receive sunlight because of their orientation and depth.

These so-called permanently shadowed regions can have temperatures of -410 °F (-246 °C), more than cold enough for cryopreservation storage.

Experts are inspired by the Global Seed Bank in Svalbard, Norway, an underground bunker that stores frozen seeds in case the Earth’s crops disappear.

In 2017, thawing permafrost threatened to flood the collection, showing that even an underground bunker could be vulnerable to climate change.

The Svalbard Global Seed Bank stores “spare copies” of valuable plant seeds in case the originals are lost

Pictured here is a vault dug into the Arctic permafrost in Svalbard that is filled with samples of the world’s most important seeds in case food crops are wiped out by a catastrophe.

Compared to seeds, animal cells require much lower storage temperatures for preservation (-320°F or -196°C).

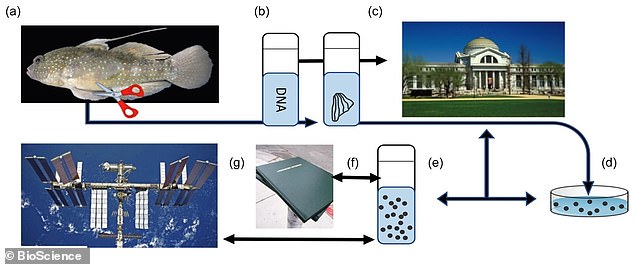

As part of their study, Hagedorn and his colleagues cryopreserved skin samples from a reef fish called the starry goby, specifically from its fins.

Fins contain a type of skin cell called fibroblasts, which produce the structural framework of animal tissues and play a key role in wound healing.

The samples will then undergo radiation exposure tests (similar to those to which the surface of the Moon is exposed) to prepare the biological material to be sent to the Moon.

Another future step is to design packaging that can withstand the levels of radiation and microgravity typical of space travel.

Samples may first be sent to the International Space Station (ISS) to see how they would hold up in space, in case changes to the packaging are needed.

Scientists cryopreserved skin samples from a star goby, a common reef fish (pictured). The samples will undergo radiation exposure tests to prepare biological material to be sent to the Moon.

Samples may first be sent to the International Space Station (ISS) to see how they would hold up in the space environment.

Finally, the first shipment of cell samples from the most endangered species could be transported along with astronauts as part of future missions to the Moon under NASA’s Artemis program.

Artemis will eventually establish a permanent base and a “sustained human presence” on the moon, with buildings and infrastructure.

Of course, the ambitious project will likely face many obstacles, including the sheer number of animal species on Earth – there are an estimated 7 million.

According to a study published in November last year, 2 million species are currently threatened with extinction, both animals and plants.

But scientists stress that this is a “programme that will last for decades” and a long-term project that will require enormous international cooperation.

“The realization of a lunar biorepository will require collaboration among a broad range of nations, cultural groups, agencies and international stakeholders to develop acceptable plans for sample preservation, governance and long-term conservation,” they say.

‘Protecting life on Earth must be a top priority in the race to build lunar sites for industry and many types of science.’