Table of Contents

Stephen Gold: If you have not remarried, there is no time limit for filing a financial relief application against an ex-spouse

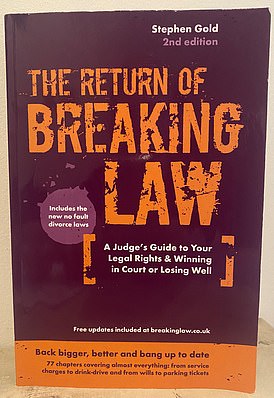

Stephen Gold is a retired judge and author who has written popular series for This is Money about how to be a successful executor, write a will, bankruptcy, consumer rights and legal disputes.

In the first part of his latest guide, he explained the basic rules that courts follow in deciding how finances are divided in a divorce and support payments to exes and children.

Today it looks at pension distribution, late applications to divide finances, remarriages and taxes.

The court must examine the parties’ pension rights, even where they will not be converted into cash in the foreseeable future.

It will also take into account any pension loss that either party may suffer as a result of the legal end of the relationship.

An example is the rights that the widow of the pension holder would have enjoyed if she had still been married to them at the time of their death rather than divorced and therefore no longer a widow.

But neither party may file a court application for financial aid.

Perhaps the party who has no pension or an equivalent pension does not know what the court might give him. Or, the existence of the pension may be hidden from the other party and, therefore, no legal claim is filed for that reason.

One of the orders that the court can make regarding a pension is a distribution order.

It is common for a percentage of the so-called cash equivalent value of pension rights to be debited from the holder’s pension and credited to a pension in the name of the other party.

Alternatively, the court could consider allowing one party to keep their pension and the other party to keep the family home.

It is possible to apply for a pension distribution order without seeking any other financial relief, such as maintenance or a lump sum.

For a detailed discussion of how it all works (although you’ll want a wet towel or flannel applied to your head every quarter of an hour or you’ll have insomnia), I recommend the free site Guide to the Treatment of Pensions in the Case of Divorce, published by the Pensions Advisory Group and recently amended. Only 192 pages.

Preventing future claims: If you don’t like acute shocks, ask for a court order even if there are no financial remedies for either party.

And for more up-to-date information on the appropriate approach to sharing, take a look at paragraphs 34 to 41 of the March 2024 judgment in a case called SP v AL (2024) EWFC 72(B).

There, the judge, who eats and breathes pensions, addressed the legal conundrum of the extent to which a party’s pension obtained outside the relationship should be excluded from a distribution order.

They and their employers may have been contributing to the pension plan for 20 years before the marriage and then continued to do so for ten years between the marriage and the divorce. Ignore 20 years of pension value when calculating which part the other party should take?

It will depend, the judge said, on whether it is a case of “needs” (see the first part of this guide in the basic rules section LINK) or whether the capital available to be distributed exceeds the needs of the party after a participation in the pension.

The judge adopted the proposal that in a case of need, it would often be fair – but not always and other circumstances could make a difference – for the full 30 years of pension to be shared out.

But in a no-needs case like the one I was deciding, the focus was likely to be on sharing depending on the length of the relationship.

You did it again?

It may be that one of the parties, after some financial remedy, has remarried or formed a new civil partnership. This, in itself, does not prevent a claim from being filed before the court, except in matters of maintenance.

They are still entitled to a fair share of the assets. They have won it. Likewise, the beginning of a permanent cohabitation does not exclude the request, not even for a maintenance order.

But pursuing support while cohabiting is probably too ambitious unless, say, the applicant has children from the previous relationship living with him, full or part-time, who are still receiving education and that inevitably increases household expenses.

Much will depend on the cohabitant’s finances and the degree to which those finances benefit the applicant.

Better late than never

If you have not made an application for financial relief within a reasonable period but now believe you should have done so, do not be discouraged. It may not actually be too late.

If you have gotten married or entered into a civil partnership without notifying the court of an application, either in the prescribed form or in the document that initiated the divorce or other marital process, you will have had one.

Too late to apply now, except (and this is a big deal) for a pension share.

However, as long as you have not married or entered into a civil partnership, there is no time limit on making an application for financial relief against your former spouse or partner.

The court might be unsympathetic if you left it for a long time and then suddenly attacked when the other party thought you were out of danger.

The delay would normally mean a discount on what would have been granted with a fast application.

A Supreme Court case in which the wife had delayed filing an application for 19 years after her divorce made headlines in 2015.

When they separated, the parties were leading a nomadic lifestyle and there was nothing in the husband’s financial circumstances to prompt the wife to bring a claim to court. But how things changed over time.

When the wife finally filed, the husband was alleged to be worth £107 million! The appeal judges gave the wife the green light to proceed with the application, holding that the wife was entitled to have her case heard even if it was exceptional.

A substantially late application would receive a decent hearing unless there were really compelling reasons against it.

So what happened in the end? Answers on a postcard? No, I couldn’t keep you in suspense. The case was settled and the wife accepted… £300,000.

The moral of the story is that while delay may not be fatal, it will not help.

And, if you don’t like sharp shocks, seek a court order, even where it is agreed that no financial remedy is appropriate for either party, dismissing all claims by both parties.

This would rule out a future application.

Tax matters

The recipient of alimony does not pay taxes on the money: conversely, the payer cannot claim relief on the alimony he or she pays.

The situation is more complicated in relation to any potential liability to pay capital gains tax when the family home (or other asset) is sold after separation.

The rules were amended with effect from April 6, 2013 by the Finance Act 2023. Provided certain conditions are met, when the asset is transferred by one party to the other, it is deemed not to involve any gain.

But where the asset is subsequently disposed of, the recipient could be subject to capital gains tax on any gains made between the date of transfer and the date of disposal, on the basis that the recipient acquired it at the original cost to the assignor.

If the property is the family home, the gain may be canceled through the principal private residence exemption that applies if the property has been the recipient’s sole or principal residence during ownership, with the exception of the last nine months. Otherwise, there may be partial relief.

That, as I say, is subject to certain conditions. These are that the transfer has been made within three tax years following that in which the parties separated; alternatively, it was part of a formal agreement or court order made in connection with the divorce or dissolution of the civil partnership.

The message, then, is that if the transfer is to take place outside of three years, enter into a formal agreement to do so or obtain a court order requiring the transfer to take place.

Other changes from April 6, 2023 concern a court order for the home to be transferred from one party to the other, but for the receiving party to grant the other party a lien (a kind of mortgage without repayments and usually without interest) on the property. .

They will usually mean that there will be no tax liability for the transferring party when the transfer is made or when the charge is made. Tax advice is recommended.

IN PART THREE… Stephen Gold explains how to reach a settlement and what happens when one ex tries to scam the other out of his or her fair share of assets.

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them, we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow any commercial relationship to affect our editorial independence.