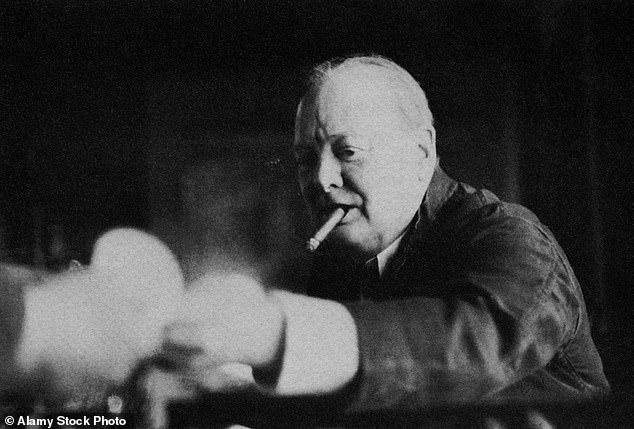

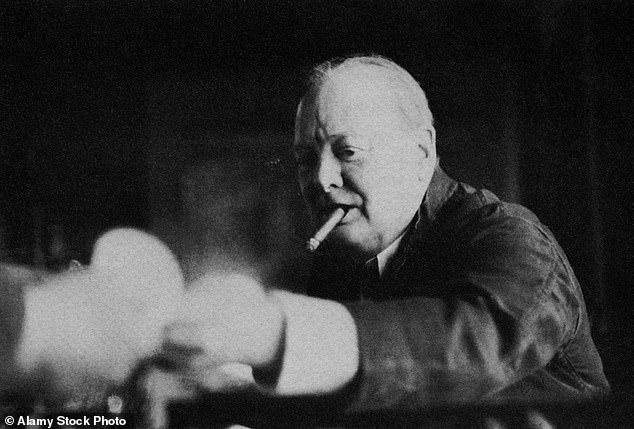

On 4 July 1940, with the possible threat of a German invasion, Winston Churchill drafted a memo to the Prime Ministers of the Dominions: ‘The Duke of Windsor’s activities on the Continent in recent months have caused HM and myself serious uneasiness as his inclinations are well known to be pro-Nazi and he may become a center of intrigue.’

As a result, the new prime minister had decided to offer the former king the governorship of the Bahamas – he had not mentioned in his memo that the alternative was a court-martial.

And so the Duke and Duchess of Windsor were exiled to the Caribbean for the duration of the war.

The Duke and Duchess of Windsor outside Government House in Nassau in 1942

It was announced that the Duke was to be Governor of the Bahamas in July 1940

The new Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, had decided to offer the governorship of the Bahamas to the Duke of Windsor. The alternative was a court martial

There was serious unrest as the Duke’s leanings were known to be pro-Nazi. The Duke and Duchess are pictured together with Adolf Hitler in 1937

The Duke and Duchess of Windsor enter Government House in Nassau in 1940

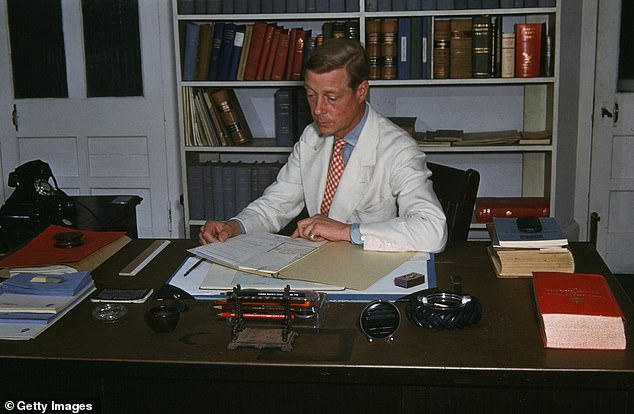

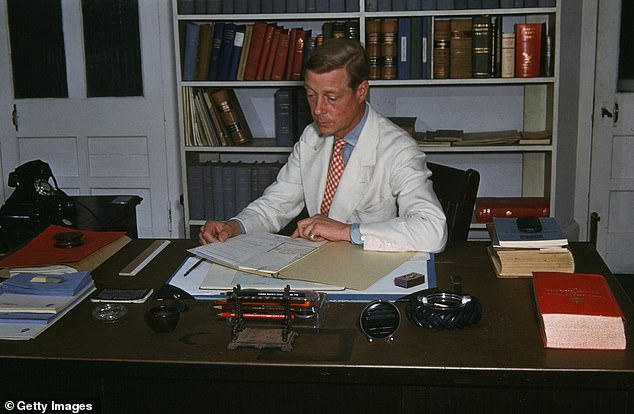

Busy at work in Government House in the Bahamas – a photo taken around 1940

Their time there has been little studied until now.

Tomorrow a Channel 5 documentary ‘Edward & Wallis: The Bahamas Scandal – Revealed’ will be broadcast based on my book Traitor King and a tranche of newly discovered documents, many from the Duke’s confidential file in the Royal Archives opened to me.

On some counts, the Windsors come out better than expected. The Duke fought to improve the situation of the black majority population, for example. Wallis volunteered at children’s clinics.

But when it comes to Windsor’s loyalty, the picture is deeply unflattering.

This is a couple who continued to maintain contacts with known German agents and lobbied to keep America out of the war.

The program reveals how Peter Russell – later professor of Spanish studies at Oxford – was accused of surveilling the pair before their arrival in the Bahamas and was ‘under orders to shoot them’ if they agreed to German overtures to become a British puppet king .

A newly discovered ‘top secret’ telegram details the extensive and meticulous German plans to help the Windsors retrieve their belongings from their home in Paris, and how Wallis’ favorite Nile green bathing suit was repatriated from their home in the South of France during what came to be called Operation Cleopatra Whim.

It also describes their extravagant spending at a time of rationing: they insisted that Government House be remodeled at the height of the Battle of Britain, when every penny of public spending went to aircraft production – and how British officials questioned how the couple financed their lavish lifestyle.

A ‘top secret’ Foreign Office telegram I recently discovered in the British National Archives asks how the couple’s US bank account had suddenly grown in one year from $1,197 to $29,931, especially given wartime exchange control rules.

There is new information about how the Duke tried to cover up the murder of Harry Oakes, was complicit in the attempt to send an innocent man to the gallows, and reveals that an FBI report and Scotland Yard file on the murder remain closed to this day .

FBI files show not only the vast extent of surveillance of the couple – personally ordered by Roosevelt – and suspicions of their continued links to the Nazi regime, but also how Windsor was blackmailed by a former mistress and how the Duke persuaded the FBI to investigate a journalist who had written a critical portrait of the couple.

The Duke and Duchess at the Waldorf Astoria in New York, two months before America entered the war

The Duke and Duchess host the annual inspection of the Bahamas branch of the Red Cross, of which the Duchess was president. Wallis volunteered at children’s clinics

Captain Edward Melchen and Captain James Barker, both of the Miami Police Department, are preparing to enter the Magistrate’s Court for the preliminary hearing in the case of Alfred de Mariog, accused of murdering Sir Harry Oakes.

Author and historian Andrew Lownie

But the program also produces fresh information about the governor’s attempts to improve economic and social conditions for the 90 percent black population against opposition from the white business cabal that ran the island, and his successful handling of a riot in 1943.

And a much more attractive picture of Wallis is presented, showing how she rose to the challenge of getting a job, working tirelessly in children’s clinics and serving in the canteen at the local air base.

The Windsors’ little-known wartime years in the Bahamas have so far been overshadowed by the abdication crisis, but as the documentary shows, they were also years of scandal.

- Edward & Wallis: The Bahamas Scandal – Revealed, Saturday 23 March at 21.15 – 22.40 on Channel 5

- Traitor King by Andrew Lownie (Bonnier Books Ltd, £10.99 and £25). To order a copy at special promotional prices of £9.89 (paperback) or £22.50 (hardback) go to www.mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937. Free UK delivery on orders over £ 25. The promotional price is valid until 06/04/2024