Archaeologists have discovered an ancient sword in Egypt that is linked to a biblical pharaoh.

The bronze blade, believed to be around 3,000 years old, bears the markings of Ramses II, hailed as the most powerful king in ancient Egypt.

Many scholars, as well as Hollywood films, have suggested that Ramesses was the pharaoh who enslaved the Israelites in the Book of Exodus.

As the story goes, Moses freed the group from Pharaoh’s control, then parted the Red Sea and delivered the Israelites to the Promised Land.

The sword was discovered among the ruins of an ancient military fort in Housh Eissa, a city south of Alexandria that contained barracks for soldiers and warehouses for food, weapons and other goods.

The shining sword found in Egypt likely belonged to a high-ranking military official during the reign of Ramses II, who some scholars believe was the pharaoh mentioned in the Bible.

Ramesses, who ruled from 1279 to 1213 BC, was known for his military power and strategic genius, leading an army of around 100,000 men.

The ancient sword probably did not belong to the famous king, but to one of his soldiers stationed at the fort, experts said.

Elizabeth Frood, an Egyptologist at Oxford University who was not involved in the excavation, said: The Washington Post:’An object bearing the cartouches of Ramesses II would suggest to me that it belonged to someone of relatively high rank.

‘Being able to display such an object, even if it was presumably in a sheath, was a symbol of status and prestige.’

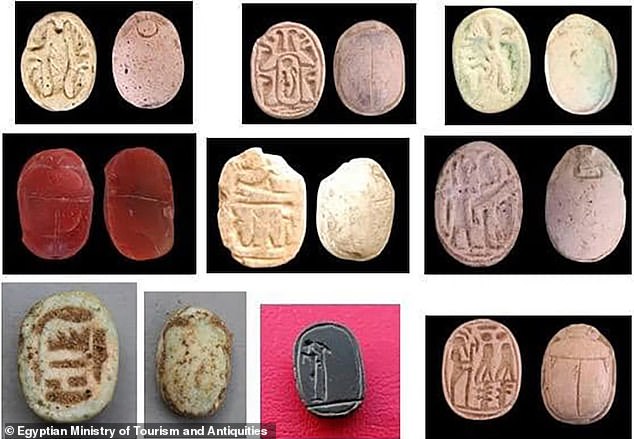

Archaeologists from Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities also discovered a treasure trove of ancient wonders, including jewelry, scarabs and protective amulets.

“In addition to the barracks, numerous artifacts and personal items belonging to the soldiers were unearthed,” the Ministry of Tourism added.

‘(These) artifacts provide insight into daily life, religious beliefs and the occupants of the fort.’

Ramesses was known to his successors as the “Great Ancestor” for leading several military expeditions and expanding the Egyptian Empire from Syria in the east to Nubia in the south.

Their most famous battle was the Battle of Kadesh, which occurred in 1247 BC against the Hittites in what is now Syria.

Ramesses personally led the charge through the Hittite ranks with some 20,000 soldiers.

But what made the fight famous was that it was one of the largest chariot battles in the world and led to the first recorded peace treaty after the battle ended in a stalemate.

Details of the Battle of Kadesh have been found engraved on ancient stones, but it has also been suggested that another record includes the story of Ramesses: the Book of Exodus.

It begins with the Israelites enslaved in Egypt, before Pharaoh, compelled by 10 terrible plagues, agrees to free them after one of the plagues kills his son and Moses leads them through the miraculously parted Red Sea.

The weapon was discovered among the ruins of an old military fort that had barracks and warehouses.

The team found other interesting artifacts at the site, including jewelry, scarabs and protective amulets.

Although no name is linked to the Pharaoh in the Bible, scholars point to Exodus 1:11 in their argument.

The passage says: ‘Then they set masters over them to oppress them with forced labor, and they built Pithom and Rameses as store cities for Pharaoh.’

Hollywood also pushed the theory in the 1956 film ‘The 10 Commandments’, naming the pharaoh after the powerful king.

Regardless, Ramses has fascinated scientists ever since his body was discovered in 1881 in a secret royal hiding place at Deir el-Bahari.

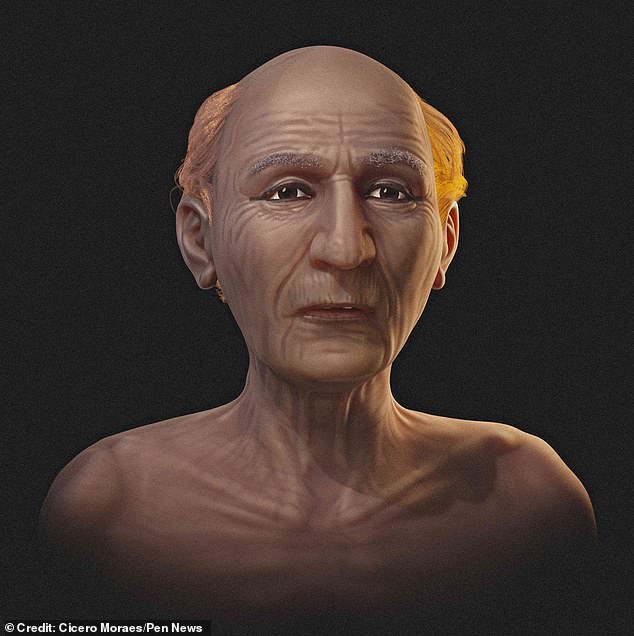

And some experts have used modern technology to resurrect the king’s face.

In 2022, Sahar Saleem of Cairo University and Caroline Wilkinson of Liverpool John Moores University used a 3D model of her skull, covering it with soft tissue and skin to recreate her appearance as an ancient Egyptian ruler.

They then reversed the aging process, turning back the clock nearly half a century and revealing what the team said was a ‘very handsome’ ruler.

A more recent facial reconstruction was performed in June of this year, but here’s what Ramses may have looked like moments before his death.

Ramesses, who ruled from 1279 to 1213 BC, was known for his military power and strategic genius, leading an army of some 100,000 men. He commissioned giant statues of himself to be built that stood in Egypt for thousands of years.

Ramesses II is also said to be the Pharaoh mentioned in the Book of Exodus which tells the story of Moses freeing the Israelites from slavery and delivering them to the promised land.

Using the same process as in the 2022 investigation, the team produced a frail, elderly man with a weathered face.

Cicero Moraes, the Brazilian graphic expert behind the new recreation, said: ‘In the present study we carried out a very extensive analysis, comparing the reconstructed face with statues of Ramses.

“The aim was to understand to what extent the statues are reliable, since many believe that the compatibility would be good. But we have seen that this is not the case: the statues indicate a good compatibility with the shape of the nose and even, in some situations, with the shape of the face.”

The statues of Ramesses II have a more delicate forehead and more pronounced lips and chin, making the features of the image “insufficiently reliable.”

In 2022, researchers reconstructed Ramses’ face when he ruled Egypt

A more recent facial reconstruction was performed in June of this year, but here’s what Ramses may have looked like moments before his death.

“We also analyzed anthropometric and DNA data from ancient Egyptian populations, and all paths seem to point to a population made up of many elements that are difficult to standardize,” Moraes said.

The team chose a skin color palette that has been seen in ancient Egyptian art, as the true shade is unknown.

The team also used information from a 1976 study of the mummified remains of Ramses, found in 1881, which restored tissues and created new bandages.

The study also determined that Ramses II had a pronounced bite and his teeth were significantly worn.

The Pharaoh also had poor dental and bone health, mainly due to an abscess, which would have caused him a lot of pain.

Although the king lived a long life, his muscles showed signs of memory loss and he had very pronounced veins on his forehead,’ Moraes and his team shared.

The team wanted to represent the aging lineups in the recreation of the king.

They collected data from hundreds of modern Egyptians to reveal the likely thickness of the pharaoh’s skin at different locations on his skull.

Another technique was anatomical deformation, in which the face and skull of a living donor, who also had a pronounced underbite, were digitally altered to match the dimensions of the mummy.

The end result is a combination of these approaches, before being appropriately aged and subjective elements such as clothing added. It reveals what Moraes called a “wise” face.