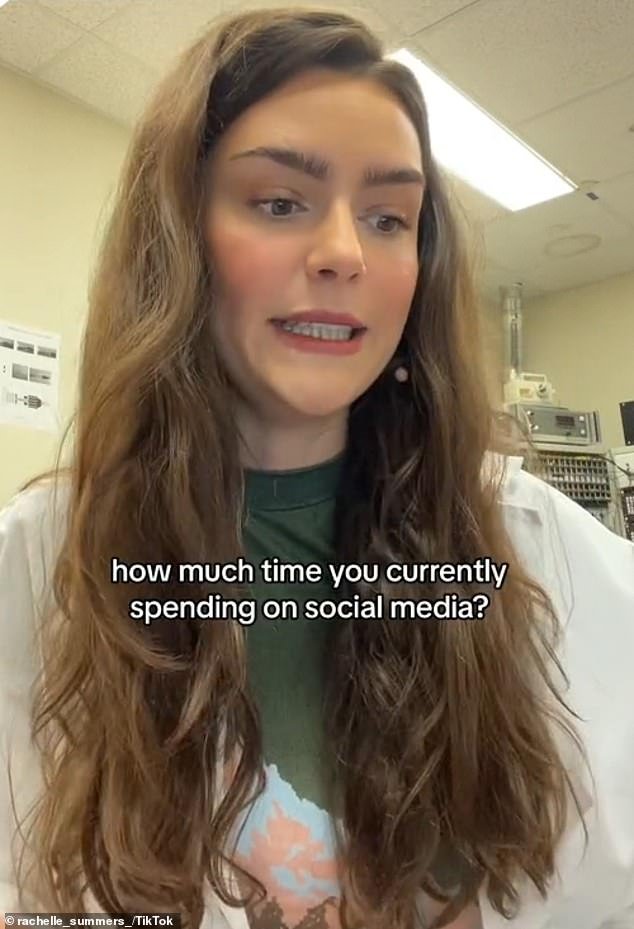

- Rachelle Summers is a medical expert who regularly shares advice on TikTok

- He recently revealed that you should spend just 30 minutes online.

- The neuroscientist pointed out that social networks can decrease your cognitive function

<!–

<!–

<!– <!–

<!–

<!–

<!–

A neuroscientist has revealed how much time you should spend on social media each day, detailing why endless scrolling can cause serious problems.

raquel summers is a medical expert who regularly shares tips and tricks to “level up” your mental well-being on her TikTok account, where she has more than 513,000 followers.

More recently, she took to the video-sharing platform to reveal that you should only spend 30 minutes scrolling through social media on any given day if you want to keep your brain sharp.

In a viral video, which has so far racked up more than 167,000 views, he explained that excessive use of Instagram, TikTok, X (formerly known as Twitter) and other platforms may be to blame for his “depression” and “anxiety.”

A neuroscientist has discovered how much time you should spend on social media each day and detailed why endless scrolling can cause serious problems.

Rachelle Summers is a medical expert who regularly shares tips and tricks to “level up” your mental well-being on her TikTok account, where she has more than 513,000 followers.

She captioned the clip: “How much social media time per day?”

‘How much time should you allow yourself per day on social media if you want to preserve cognitive function and mental well-being?

“One study looked at limiting time on social media to just 30 minutes per day, and over several weeks they saw improvements in measures like loneliness, depression, anxiety, and FOMO,” she explained.

Rachelle noted that if you want to spend more than 30 minutes on social media and still see the benefits, you should keep a “checklist” of items to make sure you don’t overdo it online.

First he said that you should set your benchmark, which will tell you how much time you currently spend on social media.

Next, he noted that you should track your sleep cycles, as well as your attention span and mood.

The neuroscientist said that if you’re sleeping poorly or experiencing “brain fog,” chances are you’re scrolling too much.

People flooded the comments section and expressed their surprise at how little they should scroll through social media.

And he added: ‘How is your mood? Are you feeling anxious, depressed, lonely or stressed? Do you notice any physical discomfort such as drainage from the eyes or headaches?

The content creator also said that if you abandon your offline relationships, then it’s probably time to cut back on social media use.

At the end of the clip, Rachel noted that if you experience any of the symptoms mentioned, you should decrease your social media use by 20 percent.

People flooded the comments section and expressed their surprise at how little they should scroll through social media.

One person said: “Brain fog is very frustrating and uncomfortable.”

Someone else wrote: ‘Ouch! I’ve been doing 30 minutes every half hour.’

Another user added: ‘Wow, I hit almost all of them.’ I’ll check my usage.’

“Thank you very much for this information,” one person commented.